About this work

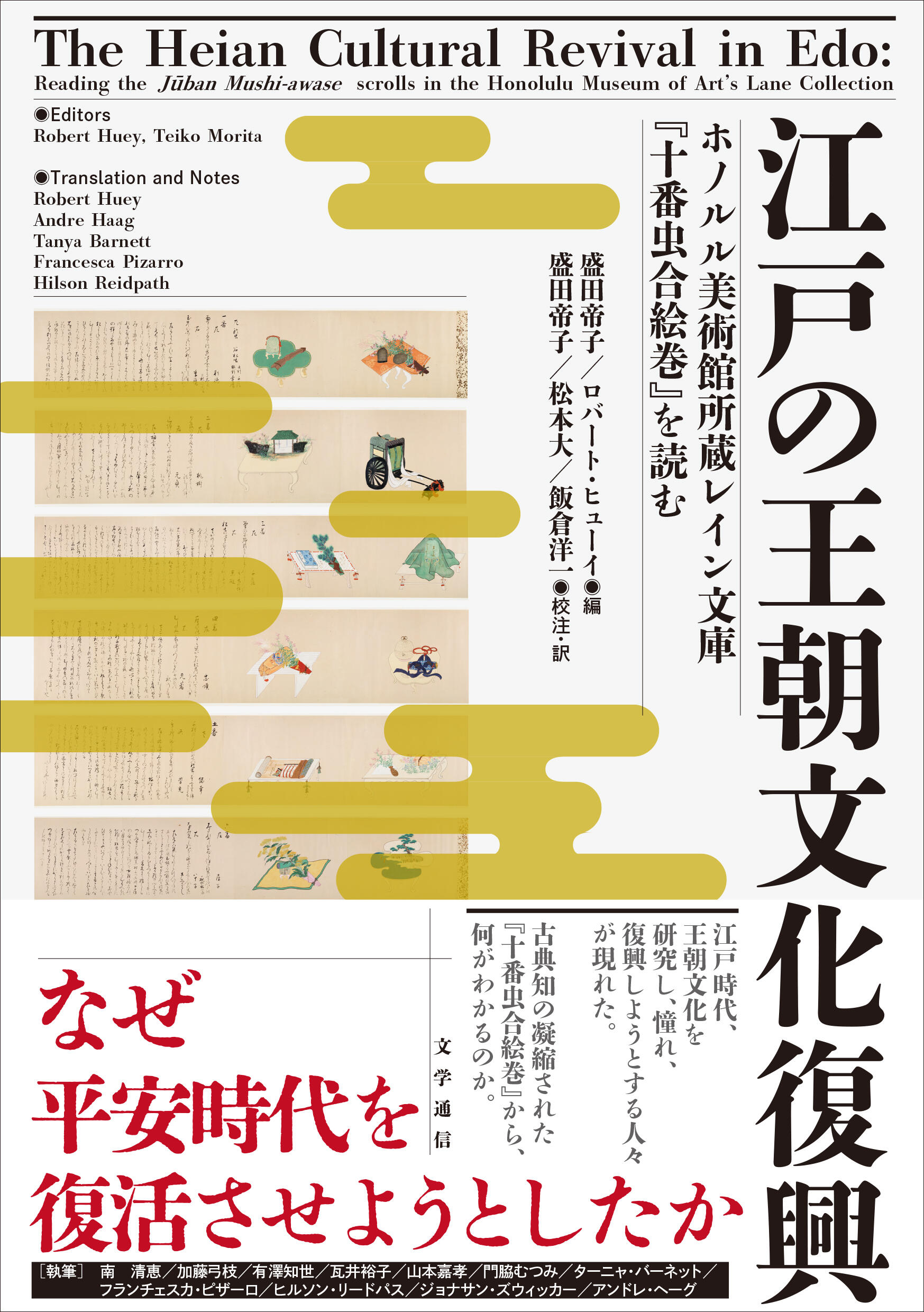

This website page describes the Jūban Mushi-awase Emaki and the institutions that hold it, as well as related books.

- The Appeal of the Jūban Mushi-awase, a Condensed Version of Classical Knowledge|Morita Teiko

- The Richard Lane Collection at the Honolulu Museum of Art|Minami Kiyoe

- The Honolulu Museum of Art

- About related books

The Appeal of the Jūban Mushi-awase, a Condensed Version of Classical Knowledge|Morita Teiko

(The following is an excerpt from "The Heian Cultural Revival in Edo" .)

1. The Popularity of Mushi Kiki in Edo and Jūban Mushi-awase

In this work, the Jūban Mushi Awase held by the Sumida River at the Mokubo temple in the Eighth Month of the Second Year of Tenmei (1782) is highlighted. This event involved participants creating a world based on classical texts alongside the Sumida River, where they competed in creating an aristocratic and nostalgic atmosphere by having bell crickets and pine crickets sing while composing waka poems. In Kyoto, there was a tradition of aristocrats collecting insects outdoors, putting them in cages, and presenting them to the imperial court as a playful activity known as mushi erami, which dated back to the reign of Emperor Horikawa. In Edo during this period, there was a trend of mushi kiki, where insect sellers roamed the streets with cages containing bell crickets and pine crickets, and people would bring cushions and saké to scenic spots in the autumn evening to enjoy the sounds of these insects.

Amidst this insect craze, and apart from the above-mentioned Mokubo-ji poets, a group of kyōka (狂歌) authors held a mushi kiki event along the Sumida River embankment on the 14th day of the Eighth Month. Following the theme of Kinoshita Chōshōshi’s Shochū Uta-awase, they composed kyōka poems expressing love by associating their emotions with insects. Although their event was published as Ehon Mushi Erami, (literally, “Illustrated Book of Selected Insects”) edited by Kitagawa Utamaro and Yadoya no Meshimori (Ishikawa Masamochi) in two volumes in 1788, it was in fact a multi-color woodblock print book depicting insects with seasonal flowers and adopting the form of a kyōka poetry contest on insect-related themes. While this mushi kiki event had been held sometime before Tenmei 6 (1786), as noted by Kikuchi Yōsuke in Utamaro: ‘Ehon Mushi Erami,’ ‘Momochidori Kyōka-awase,’ ‘Shiohi no tsuto’ (Kodansha Selection, 2018), it may have been influenced by the elegant event Jūban Mushi-awase held earlier by the Kageo group in 1782, and the recording of this event in the color illustrated scrolls Jūban Mushi-awase Emaki.

Thus, this book unfolds the story of the Jūban Mushi-awase, which may have influenced the popular culture scene in Edo at the time.

2. Jūban Mushi-awase and Its Overview Based on the Heian Period Classics

According to the postscript by Mishima Kageo, the Jūban Mushi-awase event took place after the 10th day of the Eighth Month in the second year of Tenmei (1782) along the Sumida River at Mokubo-ji. The organizer was fudai vassal Minamoto (Kawamura) Kagemasa. There were twenty participants, two assigned to each round, including daimyo, hatamoto, shogunate-approved merchants, doctors, and male and female poets, regardless of social status (refer to the “List of Participants” in this book). Originally from Kyoto, Mishima Kageo, a shogunate-approved kimono merchant, entered the service of Prince Arisugawa Yorihito in the Seventh Month of the Eighth Year of Hōei (1758) (Archives of the Imperial Household Agency Shoryōbu, Roster of Students of Prince Arisugawa Yorihito [Kan’en 2 - Meiwa 6]). Serving as the Prince’s “poetry representative” in the Kantō region, he played a central role in organizing poets affiliated with Prince Arisugawa in Edo while being a central figure in the revival of mono-awase competitions. He participated in the Ōgi-awase (Fan Contest) in 1779, the Nochinotabi Ōgi-awase (Later Fan Contest) in 1781, the Senzai-awase (Contest of Garden Plants) in 1782, the Jūban Mushi-awase in 1782, the Shunju no Arasoi (Battle of Spring and Autumn) in 1786, and the Fumi-awase (Brush Contest) in 1788, contributing to the revival of poetic competitions. He was also a patron of Suetaka, who had come to Edo in 1772 and served as a judge for poetry. Of the twenty participants in the Jūban Mushi-awase, twelve poets attended monthly poetry meetings held at Suetaka’s residence, Gikan-Tei, during the First to Seventh years of Tenmei (1781-1787). Additionally, Katō Chikage, the judge for the insect arrangements, was also close to Kageo and Suetaka. Thus, looking at the composition of the participants, the Jūban Mushi-awase event was a competition organized around the personal relationship between Suetaka and his patron Kageo, who created the Jūban Mushi-awase Emaki, and the event featured guests such as Toshinari Doi, the lord of the Kariya domain in Mikawa Province.

According to Kageo’s postscript, despite the scorching heat on that day, the twenty men and women divided into left and right teams. The left team composed waka poems inspired by bell crickets that were placed in arrangements (suhama), while the right team did the same with pine crickets placed in arrangements. The main text and illustrations reveal that the arrangements on both sides were gorgeously crafted with the high skills of artisans. On some arrangements, various plants such as plume or pampas grass (susuki) and bush clover (hagi) were planted, and live bell crickets and pine crickets were made to sing. Given the significant cost and time required to create these arrangements, it can be inferred that the poems were not composed on the spot but were prepared in advance. As the evening approached, a cool breeze blew, and when the light of the autumn moon spread throughout, participants went to the edge of the temple veranda, and while sipping saké, enjoyed the newly bloomed bush clover flowers in the garden and the charming cries of insects.

Now, consider this setting: men and women sitting together, bush clover blooming in the garden, insects singing, and participants attaching poems to arrangements that featured live plants, live bell crickets and pine crickets singing... What could have inspired such an event?

Let us examine the sources of inspiration for each arrangement in the Jūban Mushi-awase: (Bold text indicates classical works from the Heian period.)

- Left: Kokin Wakashū and Genji Monogatari; Right: “Ōi River Excursion Waka Preface”

- Left: Genji Monogatari; Right: Kokin Wakashū

- Left: Kanenorishū; Right: Kokin Wakashū Kana Preface

- Left: [Inspired by falconry implements]; Right: Shinsenzai Wakashū

- Left: Shiika Wakashū and Mumyōshō; Right: Asuji-ga-tsuyu

- Left: Tadamishū; Right: Motosukeshū

- Left: Genji Monogatari; Right: Kokin Wakashū

- Left: Shūgyoku Wakashū; Right: Shūi Wakashū

- Left: Wakan Rōeishū; Right: Shinkokin Wakashū

- Left: Genji Monogatari; Right: Genji Monogatari

3. Why the Jūban Mushi-awase Was Held at Mokubo-ji

Now, why did those who admired literary works from the Heian court choose Mokubo-ji by the Sumida River as the place to revive old practices by means of the Jūban Mushi-awase? The Sumidagawa Ōrai, published in the fourth year of Kansei (1792), contains the following entry:

The Sumida River, known as the foremost attraction in Musashi Province, has been praised by generations of poets. In particular, the excellent poem by the courtier Lord Narihira in Tales of Ise (Ise Monogatari) is widely known. Now, the Sumida River derived its name from “the river through Suda Mura.” Upstream is known as Arakawa. The temple of Umewaka-maru is called Bairyūzan Mokubo-ji. Next to the main hall, a willow tree is planted as a marker, and beneath the willow, there is a small shrine, marking Umewaka’s grave. It is an excellent Buddhist memorial. This guidebook considers this area as a foremost place and suggests that you also explore the surrounding area within a mile or two. Should you come to see it, it is northeast of Edo in Musashi Province, by the Sumida River.

The main text of the Sumida River Ōrai describes the Sumida River as the prime attraction in Musashi Province, where poets have left excellent poems for generations. It particularly mentions that Narihira, who was long considered the model for the protagonist of Tales of Ise, composed a famous poem by the Sumida River: “Capital bird, / if you are true to your name / I have something to ask you: / Is the one I love back home / still there or not?” (Na ni shi owaba / iza koto towamu / miyakodori / waga omou hito ha / ari ya nashi ya to). In the latter half of the 18th century, those who aspired to the elegance of the imperial court found the image of the Narihira character standing on the Sumida River bank and longing for Kyoto to be appealing. A century before them, waka poets of the Tōshō school, such as Konoe Nobutada and Prince Arisugawa Yukihito, had also composed poems longing for the capital (Kyoto) from the banks of the Sumida River (collected in Murasaki no Hitomoto), in imitation of Narihira’s. Thus Kageo and his colleagues considered the area along the Sumida River – a place associated with longing for the ancient imperial court – to be an ideal location to revive Mushi-awase.

Furthermore, the Sumidagawa Ōrai (Kansei 4 edition) depicts the “Eight Scenic Views of the Sumida River” seen from Bairyūzan Mokubo-ji. The text mentions a willow tree next to the main hall of Mokubo-ji along the Sumida River, with a mound for Umewaka underneath. The view from Mokubo-ji was considered the best scenic spot along the Sumida River. Considering the description in Kageo’s postscript, where he mentions going out to the veranda of Mokubo-ji where the Sumida River is visible, drinking saké while enjoying the autumn moon, the garden’s bush clover, and the sounds of insects, it seems that Mokubo-ji, historically known also as a resting place for falconry during the hunting excursions of the Tokugawa shoguns, was an appropriate location for them to revive the long-lost Mushi-awase tradition.

4. The Design of Jūban Mushi-awase as Seen through its Poetry and Illustrations

From the waka (31-syllable poems) presented in connection with the arrangements, we can extract expressions for different times of day in the first and second volumes. The following are examples:

[First Volume] (First half of the event) → Expressing the time period around sunset and before moonrise

| Round 1: Left “Dew,” | / Right “Cricket awaiting the moon” |

| Round 2: Left “Evening dew,” | / Right “The moon not yet risen” |

| Round 3: Left (no specific time), | / Right (no specific time) |

| Round 4: Left “Evening voice,” | / Right “Autumn evening” |

| Round 5: Left (no specific time), | / Right, “Evening dew” |

[Second Volume] (Second half of the event)→ Expressing the time period after moonrise, midnight, and late-night

| Round 6: Left “Midnight in autumn,” | / Right (so specific time) |

| Round 7: Left “Evening dew,” | / Right “Night deepens as the moon crosses the sky” |

| Round 8: Left (no specific time), | / Right (no specific time) |

| Round 9: Left (no specific time), | / Right (no specific time) |

| Round 10: Left “a thousand nights pass,” | / Right “the moon reflected on the dew-drenched garden” |

Now, let’s examine how the live bell crickets and pine crickets, placed in the arrangements, were expressed in the waka.

Round 1, Left (Toshinari): “crickets trill”

Round 1, Right (Suetaka): “notes of the pine cricket”

Round 2, Left (Momoki): “the trilling of bell crickets”

Round 2, Right (Motosada): “chirping pine cricket”

Round 3, Left: (Chikage): “the bell cricket cries out”

Round 3, Right (Kageo): “cries of the chirping pine crickets”

Round 4, Left (Ch・jun): “like a bell… its evening voice rings out”

Round 4, Right (Gencho): “crickets’ cries”

Round 5, Left (S・k・): “bell crickets… singing”

Round 5, Right (Yoshimitsu): “crying… pine cricket”

Round 6, Left (Fusako): “intermingled cries of bell crickets”

Round 6, Right (Yasoko): “voice of the pine cricket”

Round 7, Left (Yoshiaki): “bell crickets’ trills”

Round 7, Right (Masanaga): “pine crickets chirp”

Round 8, Left (Masatsune): “trilling songs of crickets”

Round 8, Right (Ariyuki): (no sound words)

Round 9, Left (Chisen): “trilling of bell crickets”

Round 9, Right (Mitsuru): “songs of pine crickets”

Round 10, Left (Toyoaki): “bell crickets trilling”

Round 10, Right (Kagemasa): “pine crickets’ tearful cries”

In almost all of the twenty waka from the first through the tenth rounds, expressions like “trilling of the bell cricket” and “chirp of the pine cricket” are included, depicting the scene of the insects making noise. The only exception is the poem on the Right in Round Eight, by Ariyuki: “What a pleasure / it would be to spend / a thousand autumns here. / Today, at last, the crickets / that I’ve so ʻpinedʼ for!” (Tanoshisa wa / chitose no aki no / koko ni hemu / matsu chō mushi ni / kyō wo machiete).

In the original poem, there is no verbal expression of the sound or appearance of the pine cricket. This waka in fact received a negative judgment. On the other hand, the commentary for the poem on the Left in Round Ten, for example, says, “in the Left poem the hum of insects can be heard throughout the composition from start to finish, so the various participants were urged not to shift the Win over to the guest [Toyoaki],” suggesting that the accurate representation of the sounds of bell crickets and pine crickets was one of the crucial points in determining the victory or defeat of the waka.

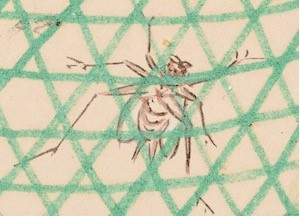

Now, let’s take a closer look at the enlarged photos of the live bell cricket from the Left team’s arrangement, and live pine cricket from the Right team’s arrangement in Round One.

What we can see in the illustrations are a bell cricket and a pine cricket with spread wings. The depiction accurately reflects the movement of the wings when bell crickets and pine crickets make noise. Thus, in the arrangements presented along with the waka, live bell crickets and pine crickets were indeed making noise at that very moment. The waka had to be composed with the assumption that bell crickets and pine crickets were currently making noise.

Conclusion:

In 1942, Andō Kikuji introduced the Kageo’s postscript from the Jūban Mushi-awase, and now, eighty-three years later, with the collaboration of many individuals, we are able to share the original photographs, in a critical edition, with transcription, modern language translation, commentary, English translation, and the public exhibit of the Jūban Mushi-awase Emaki on the Honolulu Museum of Art’s website. In the latter half of the 18th century, people in Edo, inspired by the court culture of Kyoto, creatively reconstructed imperial court literature across time and space. By considering the sensory aspects of vision, hearing, smelling, and the touch of the autumn wind, and delving into the performances on the day of the event, we hope you can appreciate the condensed classical knowledge in the captivating Jūban Mushi-awase Emaki.

※ This response includes parts based on the findings of the Jūban Mushi-awase Emaki Study Group and Annotation Review Committee. I express my deep gratitude to all participants.

※ In composing this manuscript, I extend heartfelt thanks to HoMA for granting permission to view the scrolls and include photographs in this book. The published photographs of the Jūban Mushi-awase Emaki held by the Honolulu Museum of Art (photographed by Scott Kubo) are based on the Collection of the Honolulu Museum of Art. Purchase, Richard Lane Collection, 2003 (TD 2011-23-415).

※ This manuscript is an abridged version of the Japanese "解題" (Introduction). We encourage scholars who can read Japanese to read the longer version, as well, since it contains more detail.

(Figure1)Round One, Left, Bell cricket

(Figure2)Round One, Right, Pine cricket

The Richard Lane Collection at the Honolulu Museum of Art|Minami Kiyoe

(The following is an excerpt from "The Heian Cultural Revival in Edo" .)Opened in 1972 in Hawaiʻi, U.S.A. by Anna Rice Cook (1853–1934), daughter of a missionary family, the Honolulu Museum of Art (HoMA) is accredited by the American Alliance of Museums. The collection exceeds 50,000 pieces spanning 5,000 years. Among them, the collection of Japanese art is particularly noteworthy. In 2003, approximately 6,000 titles of Japanese woodblock-printed books, mainly from the Edo period, 3,000 Japanese, Chinese, and Korean paintings, and 850 shunga (erotic art) and ukiyo-e collected by Dr. Richard Douglas Lane (1926–2002) were added to HoMA, which now is home to one of the largest Japanese art collections in the United States, both in quality and quantity. Jūban Mushi-awase Emaki (picture scrolls of A Match of Crickets in Ten Rounds of Verse and Image) is also included in the Lane Collection.

1. Richard Douglas Lane

Richard Lane was a prominent figure in the postwar Japanese art world, a scholar of ukiyo-e, a collector and an art dealer. He was born in Florida in 1926, grew up in Queens, N.Y., and served in the U.S. Marine Corps as a Japanese interpreter during World War II. After the war, he studied Japanese and Chinese at the University of Hawaiʻi, and then went on to study Asian languages at the University of California, Berkeley, the University of Michigan, and the University of London. He received his M.A. in Japanese Literature from Columbia University in 1949 with a study of Ihara Saikaku (1642–1693). From 1950 to 1952, he studied Japanese literature at the University of Tokyo, Waseda University, and Kyoto University, while interacting with Edogawa Rampo (1894–1965) and Itō Seiu (1882–1961). He taught elementary Japanese language and culture at Columbia University from 1953 to 1954 as Donald Keene’s (1922–2019) predecessor. He then received his PhD in classical Japanese literature from Columbia University in 1958. When James A. Michener (1907–1997), Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Tales of the South Pacific (1947), donated 5,400 ukiyo-e to HoMA, Lane joined the staff of the museum in 1959 and continued to research and catalog Michener’s ukiyo-e collection until 1971. Exchanges between HoMA and Lane continued thereafter. Known for his many excellent academic publications, including Images from Floating World: The Japanese Print (1978) and Hokusai: Life and Work (1989), Lane was fluent in reading kuzushi-ji (characters written in cursive style) and seal scripts on ukiyo-e. With a deep knowledge of classical Japanese art and literature, Lane made many accomplishments as a scholar.

2. The Richard Lane Collection

Lane, who lived in Yamashina, Kyoto in his later years, died of chronic heart disease in 2002 after 76 years of life. He was predeceased by his wife and died without a will or heir. Therefore, HoMA, with whom he had a close relationship, purchased his collection, and it was transferred to Hawaiʻi. The greatest feature of his collection are Japanese woodblock-printed books from the 17th to 19th centuries, especially rich in illustrated books from the 17th century, such as Moronobu ehon (books illustrated by Hishikawa Moronobu [?–1694]). There are also a number of rare kurohon and aohon (both are illustrated popular fiction published during the Edo period) that only exist in this collection. The diversity of the Lane Collection is reflected in the many categories. For Chinese art, there are Chinese Buddhist and Daoist paintings of the Yuan (1271–1368) and Ming (1368–1644) dynasties as well as Chinese landscape paintings. The collection of Korean art includes a rare Korean painting from the Joseon dynasty (1392–1897) depicting a gathering of scholars. There are also Japanese paintings of the Kanō school in Kyoto, collected under the influence of Lane who spent the later years of his life in Kyoto. In addition, there are Japanese picture scrolls such as Jūban Mushi-awase Emaki that show the revival of Heian court culture in Edo period, shunga, which have made it possible for HoMA to hold three special exhibitions, and ukiyo-e from the end of the Edo to the Meiji period. The vast Lane collection is still under research, and thus its expanse is not yet known. Under such circumstances, it is very gratifying to see one of the works in the collection spotlighted, and the results of the research introduced to the world in this book. Lane’s achievements as a scholar are already internationally recognized, so Lane would have been delighted that the excellence of his collection will be made known to the world .

The Honolulu Museum of Art

The Honolulu Museum of Art (HoMA), which is accredited by the American Alliance of Museums will celebrate its 100th anniversary in 2027. The territory of Hawai‘i chartered HoMA in 1922 and opened it to the public on April 8, 1927. HoMA is a unique gathering place where art, history, culture and education converge and strive to be a vital part of Hawai‘i’s cultural landscape. It was the vision of the founder, Anna Rice Cooke (1853–1934), a woman born into a prominent missionary family on O‘ahu. Growing up in a home that appreciated the arts, she went on to marry Charles Montague Cooke (1849–1909), also of a prominent missionary family, and the two settled in Honolulu. They built a home on Beretania Street, on the site that would become home to HoMA. This building is registered as a National and State Historical Site.

As Charles Cooke prospered, Mr. and Mrs. Cooke began to assemble an art collection. When the Cookes’ art collection outgrew their home and the Cooke Art Gallery at Punahou School, Anna Rice Cooke decided to create Hawai‘i’s first visual arts museum, which would reflect the islands’ multicultural make-up, for the children of Hawai‘i. Since it opened, HoMA has grown steadily, both in acquisitions and in stature, becoming one of the finest museums in the United States. Additions to the original building include an expansion to the library, a gift shop, a cafe, a contemporary gallery, 292-seat theater, and the Honolulu Museum of Art School for studio classes.

The Museum’s permanent collection has grown from approximately 875 works to more than 50,000 pieces spanning 5,000 years, with significant holdings in Asian art including Japanese ukiyo-e prints by renowned artists like Katsushika Hokusai and Utagawa Hiroshige, ranking third in the nation in terms of holdings, as along with Chinese paintings from the Ming and Qing dynasties, and Korean ceramics from Goryeo dynasty. The Museum is also home to European paintings by artists such as Claude Monet and Vincent van Gogh, as well as American paintings by James McNeill Whistler and John Singer Sargent, among others. Its contemporary art includes multimedia, while its traditional works encompass pieces from Hawai‘i, Africa, and Oceania. Additionally, the HoMA collection houses a variety of art forms, among them textiles, decorative arts, and more.

HoMA continues to reflect Mrs. Cooke’s vision by being dedicated to the collection, preservation, interpretation, and teaching of the visual arts, and the presentation of exhibitions, performances, films, and public programs that serve Hawai‘i’s diverse communities.

About related books|“The Heian Cultural Revival in Edo”